This website is a useful place for finding my contact information, my social media feeds, my professional biography, and an occasionally-updated selection of my published work. If you’re looking for a way to keep up with my writing, the best way to do it is by signing up for my free politics newsletter here.

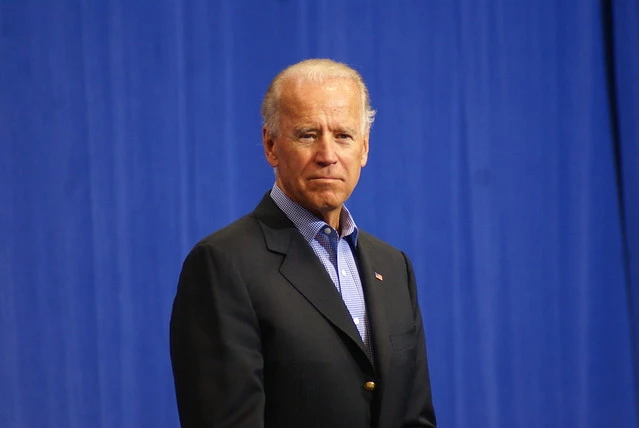

How should the left think about rallying behind Biden?

This is an essay from my weekly newsletter, which you can read in full here and subscribe to here.

In the wake of Bernie Sanders dropping out of the race, there’s been considerable commotion over whether or not Biden should be endorsed, supported, or voted for among leftist commentators and activists.

Strikingly, Sanders’s campaign press secretary Briahna Joy Gray said she could not bring herself to personally endorse Biden, putting her at odds with her former boss. A number of leftie pundits have made it clear that it should not be taken as a given that Sanders supporters will consolidate behind Biden come Election Day, and that they still must be won over. The trending of #NeverBiden on Twitter may have helped inspire The Intercept’s Mehdi Hasan to interview Noam Chomsky, who argued that declining to vote for Biden is a vote for Trump — which in turn incensed some activists on the far left. (Note that Chomsky has historically always backed the idea of voting for a Democrat over a Republican in presidential elections.)

Is there a serious chance of Sander supporters abstaining from voting in the general election en masse? I’d wager no. Some liberals love to bash Sanders for the Dems’ 2016 loss, but Sanders campaigned for Clinton and in 2016, his supporters stayed at home, voted third party or voted for the Republican candidate at a lower rate than Hillary Clinton supporters did in 2008 after Obama won the nomination. Those Sanders supporters who defected to the GOP were primarily offbeat moderates, not diehard, ideologically coherent progressives. And this time around, the crisis of Trump and a global pandemic should further counteract some of the temptation to shun the Democrat. It’s also worth noting that many of the most vocal #NeverBiden folks might be people who don’t generally vote and don’t actually represent the threat of people leaving the party in droves.

Still, the ethics of presidential voting is a perennial debate on the left, and it’s not a trivial one. The US has appallingly low voter participation rates, and presidential contests skew extra competitive in this era due to the lovely anti-democratic cocktail of party polarization and the electoral college, so it’s worth making an affirmative case for why even the most disenchanted lefties and Sanders supporters — even those who completely despise the Democratic Party — should vote for Biden. In my opinion, it’s a no-brainer. Continue reading “How should the left think about rallying behind Biden?”

Why did Bernie lose?

I’ve spent my entire politically sentient life thinking about and studying theories of radical change. It is not an emotionally rewarding undertaking. Most of it is spent investing oneself in an idea whose promise is fleeting (developing the perfect protest model!) or banking on the revival of something that feels far gone (militant sector-wide organized labor!). Hopes are dashed all the time; the power of capital feels impenetrable. Bernie Sanders provided that rarest of things for me: an answer.

Sanders demonstrated clearly that the anticapitalist left has a real way to effect change in American political life right now. That it’s possible for the left to make inroads in the two-party system, and that it’s possible to engage in high-level electoral politics without entirely defanging oneself. Sanders didn’t win the presidency, but he came astonishingly close, and in the process he reshaped the Democratic party platform and fueled the rise of an exuberant left-wing bloc in Congress that advocates for taxing the hell out of the rich, Palestinian liberation, and seriously reckoning with climate catastrophe.

Sanders radicalized a significant swath of the citizenry more efficiently than any other leftist movement or uprising in recent memory. I hope it’s evident for many generations to come that the left should not ignore the electoral sphere or make third party bids but compete with Democrats in contests where they can launch viable challenges. Developing a radical wing of the Democratic Party and competing directly for the presidency is just one piece of the puzzle when it comes to building a fundamentally more just society. But it’s not a small one, and it could potentially be a very big one.

That all being said, Sanders lost — and eulogizing is not the best way to build on Sanders’s work and legacy. What’s needed is a careful and honest evaluation of what did and didn’t go right in this presidential bid. So far it’s not clear that’s happening.

It’s understandable that activists and commentators on the left are sad about Sanders ending his five-year campaign for the White House. But some of it is veering close to tantrum-throwing. The most troubling phenomenon is the stream of complaints that the Democratic primary was rigged, and that the party establishment was unacceptably vicious and unfair in its fight against Sanders.

I’m honestly surprised by these accusations. I have seen no credible reports or evidence of vote-rigging in any nominating contests, nor do I think pulling off something so complex and difficult-to-cover-up as stealing an election is something state parties are competent or ideologically monolithic enough to carry out. Super-delegates did not sway voting in the race, due to post-2016 rules changes. There were almost too many debates this time around compared to 2016, and the terms for entering the debate were sensible (with the exception of the eventual move to ensure the inclusion of Bloomberg later on, which ironically backfired for him). Some pundits have painted the moderate consolidation around Biden before Super Tuesday as shady or inappropriate, but in reality it was just smart politics — the left should hope to develop that kind of discipline next time a Warren-Sanders type dilemma arises.

Winning elections in America is an ugly business, and treatment of Sanders in this primary season did not strike me as uncommonly nasty. Political parties routinely use voter roll purges, voter caging, deceptive robocalls, and racist and misogynistic advertising to gain advantage over their opponents. The red-baiting against Sanders was underhanded and in bad faith — but what else did you expect? I didn’t consider it as disturbing as Clinton campaign’s leaks of photos of Obama in Somalian garb in 2008.

Sanders had a decent shot this time around: he had exceptional favorability ratings, huge name ID advantage, and he had plenty of cash — but he didn’t win enough votes. That’s what it comes down to.

Why Sanders lost will be debated for months and years to come. Here are some preliminary thoughts:

Sanders only had one speed as a rhetorician

Sanders’s unchanging views, laser focus on the same set of themes, and famous disinterest in talking about anything other than power and policy bestowed him with an amazing asset that underpinned his high favorability ratings: the perception of being an honest politician. Even Republicans terrified of his big government promises regularly admitted they saw him as a true public servant.

This tendency also has its costs in a highly competitive election. Sanders showed almost no ability to effectively deploy stories, data, arguments and narratives that responded to the contingencies of world events and the currents of the election cycle. (As an example, my mom told me that she really wanted to give Bernie a chance during the post-coronavirus debate, but found that she wasn’t comforted by his brusque tone and his usual hammering away at Medicare-for-all, a policy she’s heard about for half a decade.) In debates and speeches, Sanders rarely dialed down his anger, showed nuance or revealed his true emotional depth. He only reluctantly talked about how his personal story explains his views and would shape his leadership style. Personally, I share Sanders’s preference for sticking to policy, but the world we live in cares about other qualities of a politician as well.

In his 2016 run, Sanders’s demonstrated that plainly owning his radical ideology didn’t kill his candidacy, and in many ways strengthened it in time of rising populism. But in order to seal the deal — especially in an era of crisis when many voters were fixated on feeling safe about “electability” — Sanders needed to be a far more multidimensional orator to win over skeptics.

The political revolution theory didn’t pan out

Sanders’s strategy for winning the election was a mass mobilization of his base and disaffected and first-time voters, fueled chiefly by Americans who most badly needed the revolution — the young and the working class. But that didn’t work out.

In general in the first several nominating contests — where Sanders performed his best — he was only narrowly winning first-time voters, he wasn’t driving higher turnout overall, he wasn’t capturing regional upticks in turnout, and there wasn’t a discernible youth surge.

Then on Super Tuesday, where Sanders effectively lost the primary, the numbers were damning. New York‘s Eric Levitz broke it down well:

The candidate of the multiracial working class beat the polls — and overcame his rival’s massive financial advantage — by achieving record turnout through the mobilization of first-time primary voters.

But that candidate turned out to be Joe Biden.

According to exit polls, the former vice-president won non-college-educated whites in Old Dominion by a 42 to 34 percent margin, and working-class African-Americans in a landslide. Meanwhile, turnout in Virginia nearly doubled between 2016 and 2020, and Biden won a slim majority of first-time Democratic primary voters.

These trends were not uniform across Super Tuesday states. But Biden won working-class Democrats in more states than Sanders did, and Uncle Joe tended to do better where turnout was higher. At the same time, the Sanders campaign failed to translate four years of movement building — and more financial resources than any rival but Bloomberg — into higher youth turnout than it had inspired in 2016. In the senator’s home state of Vermont, voters under 30 comprised 10 percent of the electorate Tuesday, down from 15 percent four years ago.

The failure of young voters to turn out was probably the most predictable. While Sanders’s lock on the youth vote was the most symbolically powerful asset of his campaign, his reliance on it was always his biggest electoral liability, given historical trends.

While Sanders became a big part of Gen Z / millennial identity and social media presence after 2016, that crowd did not deliver the goods at the polls.

Targeting new and disaffected voters was also a huge gamble. It’s inherently risky to bet on winning by relying on people who are new or establishment-skeptical or resource-poor voters. Mobilizing this set is by definition harder than mobilizing voters familiar with the electoral process (from registration deadlines to how to navigate a caucus) and with greater resources to actually make it out to cast a ballot (time, access to transportation, daycare for children, etc.).

Messaging that focuses on working class concerns isn’t enough. When you’re talking about communities that are effectively disenfranchised by structural and economic factors, voter mobilization operations might be coming too late in the pipeline for a candidate to funnel them into the electoral process. (This is a place where traditionally organized labor would play a huge role in community organizing and developing a positive political program before any election.) An electoral strategy that centers on attracting non-organized working class people is always going to burdened by a resource-based Catch-22: poor Americans lack the very resources to vote for the policies that would allow them to vote in the first place.

This doesn’t mean giving up on this as an electoral strategy, but it means looking closely at how to improve it in the long run. It should also give pause to Sandernistas who say they “don’t need” to build coalitions with ideologically adjacent voters like Warren supporters .

Trouble with the “black vote”

For the second primary season in a row, Sanders got completely rocked by the establishment candidate among black voters.

The reason I put black vote in quotes is because black voters are treated as a monolith by mainstream pundits when a) black voters are not in any way ideologically homogenous b) black voters aren’t, as the casual use of the term sometimes implies, voting based purely on “black concerns.”

Sanders did make sincere and sustained efforts at outreach to black voters with his staffing, surrogates, and policy emphases, but it didn’t work for him. He still got clobbered by Joe Biden among black voters all over the country, and it was decisive over and over again in the South.

But it’s important to note that Sanders performed much better with black voters outside the South than in the South, and most black Democrats under 30 supported Sanders. That’s a clue that perhaps the underlying issue here is a struggle to win over conservative and moderate voters.

In the South — where black voters often constitute a plurality or majority of the electorate — Democrats are more moderate and conservative than outside the South, more religious, and more likely to view working with the Republicans who dominate their region as something that’s achieved by staking out centrist positions.

On top of ideological trends, there’s the issue of party affiliation. Vox‘s Matt Yglesias has argued that Sanders’s hostility to the party apparatus likely alienates a lot of moderate black voters:

The problem extends beyond outreach strategies to the fundamental content of Sanders’s political message. As political scientists Chryl Laird and Ismail White show, black Democrats are, on average, less left-wing than white Democrats. At the same time, for historical and sociological reasons that Laird and White explore in their excellent new book Steadfast Democrats: How Social Forces Shape Black Political Behavior, black Democrats have warmer feelings toward the Democratic Party as an institution.

To summarize the story extremely briefly, most white people are Republicans. Those who are not Republicans have made a very conscious ideological choice to reject conservative ideology, creating a largeish bloc of voters who — like Sanders himself — are left-wing but cool on the Democratic Party. By contrast, black people who participate in black institutional life — who attend black churches, have many black friends, live in black neighborhoods, etc. — tend to have a strong affirmative attachment to the Democratic Party, even as their policy views are diverse.

The essence of Sanders’s message is that progressive-minded people need to overthrow a corrupt Democratic Party establishment in order to remake it in a more ideologically rigorous direction. This is just antithetical to the main currents of black opinion and the main modes of black political engagement.

Consequently, despite years of earnest striving to win over black voters, Sanders ended up over the weekend speaking to a room full of white people in majority-black Flint, Michigan.

I don’t have any answers at the moment, but I think that discussion of the left winning “the black vote” needs to be placed in geographical, ideological, material and political cultural contexts to be of any use. “Just find more black surrogates and talk about criminal justice” is degrading to both black voters and the left.

The absence of a popular front with Warren

Sanders and Warren had a non-aggression pact that held together for most of the primary season but unraveled right before the nominating contests actually began, and that probably hurt Sanders.

The Warren campaign’s leak of the conversation in which Sanders allegedly said a woman couldn’t win against Trump — which, by my lights, was a clearly coordinated campaign effort since it involved four sources from a highly disciplined campaign — was a desperate maneuver that did not benefit Warren, but likely made more of her serious supporters more hesitant about pivoting to Sanders. (A quick note on the ethics of the move: I think if Warren truly felt that Sanders was out of line in that conversation, she should not have allied herself with him and brought it up at the beginning of 2019 in a nuanced, constructive and contextualized manner; the last-ditch leak, bereft of context, right before the contests began, struck me as a cheap move to use against a politician she shared so many views with.)

I don’t know who is to “blame” for failing to develop a stronger alliance between the two, and it’s possible that their pact was always bound to fail because Warren saw herself as on a fundamentally different path despite their overlapping visions. But if things had gotten less ugly between the two, and Warren had folded and endorsed Sanders early in the race the way that the moderates did with Biden, that could have given Sanders a substantial boost.

But it wasn’t just about the candidates — it was also about their supporters. As I wrote in my last newsletter, I do think that a toxic Sanders culture online was a real problem and likely hurt Sanders’s ability to attract Warren supporters at later stages in the race. I also don’t buy the idea that it’s purely a media phenomenon or that “nobody is on Twitter,” something I touched on in my last newsletter and my piece for GQ:

Exit polling from several states indicates that 10-20 percent of primary voters follow political news through Twitter. Not all those people are likely to be plugged into the exact corners of Twitter that experience or discuss the issue of rancorous Bernie supporters. But income and education trends on Twitter suggest there is a disproportionate amount of Warren-friendly users on Twitter in general.

We know that there are many Warren supporters online who have complained about venomous Sanders supporters and explicitly cited it as a reason that they’re reluctant to or opposed to backing Sanders. There’s also been reporting that suggests this set is turning people away from his candidacy. “Lots of people at Warren and Pete town halls I talked to were weighing a Sanders vote but said they were turned off by the culture and crowds,” Sam Stein, the politics editor of the Daily Beast, tweeted in February. When I wrote about the issue as a liability for Sanders’s ability to expand his base, I saw some former Sanders supporters online explain that it’s why they migrated to Warren. “Bernie Bros definitely pushed me to the Warren camp,” tweeted Twitter user Meerenai Shim, whose bio says she lives in Campbell, California, and noted that she voted for Sanders in 2016.

There’s plenty more to discuss, but those are some thoughts that are top of mind.

If the left wants to keep up the momentum and improve itself, it needs to reckon with this loss rather than pout, to be introspective rather than fixate on scapegoats. While mainstream liberal media was indeed unethical in its approach to covering Sanders, the primary race was probably as fair as any contest of the kind will get.

This essay was featured in my politics newsletter, which you can sign up for here.

The Bernie Bro problem is real, and it could destroy the left

Bernie Sanders’s online supporters are a tremendous campaign asset. Their extraordinary numbers and hyper-connectedness have helped power a jaw-dropping fundraising behemoth. Their passion is a reminder that Sanders might be the only candidate with a real base in the race. And their ubiquity on social media serves as a counterweight to the bourgeois press’s open war against the promise of social democracy.

But some of them are also a liability.

The infamous Bernie Bro archetype that originated during the 2016 primaries is once again rearing its head — and there are many signs that an ascendant leftist movement is underestimating how much damage it could do to their cause.

Back in 2016, the context and the meaning of the term were different. There were two premises to the charge: (1) Sanders’s support was disproportionately white and male and (2) These white men were rude and aggressive and were typically inattentive to the experiences of racial minorities and other marginalized groups.

There was some truth to the first claim. During that primary season Sanders’ supporter base skewed white and male. The second claim I didn’t find convincing, and seemed overly reliant on a handful of reporters’ anecdotal sketches.

Overall, the charge of Bernie Bro was a crude weapon employed by some Hillary Clinton supporters. It failed to take into account how there was real diversity in the core of Sanders’ base: young people. And what vexed me most was that it effaced the many nonwhite and women lefties — both online and offline — who made a compelling case for Sanders based precisely on antiracist and feminist critiques.

This time around, the Bernie Bro charge is different. It’s widely known that Sanders supporters are extremely diverse in terms of gender and race and class, and the notion that only those “privileged” can afford to adopt a more radical worldview has been revealed to be absurd, as it always was. The second prong of the archetype has manifested again, though, but in a different form. Now the claim is that Sanders supporters online are disproportionately likely to be cruel and obnoxious, or bully and harass people.

Unfortunately I think this claim has some legitimacy. And I think that the many Sanders supporters online who are going to lengths to rationalize or defend the adversarial style are too plugged in to the incentives of social media popularity contests and out of touch with what it will take to win an election and build a sustainable leftist movement. Continue reading “The Bernie Bro problem is real, and it could destroy the left”

Notes on Pakistan

I find all travel to be profound, but my trips to Pakistan occupy a special plane. What does it mean to return to a home in which you never lived? I sip on chai and soak up the pleasant dizziness that comes from watching the axes of time and space torn from their tracks.

Growing up, my family and I used to travel to Pakistan, the country of my parents’ birth, every summer or every other summer. But after my parents divorced in high school, I’ve visited much less frequently. It has made every subsequent trip harder-hitting.

This trip I thought about Orwell’s classic aphorism, “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” I’ve practiced mindfulness meditation on and off my entire adult life, but in the last year or so it has become a daily practice, and has grown intertwined with my consciousness. I anchor myself by paying attention to my breath, by listening intently to the clatter of the subway, by trying to feel a brisk wind whipping my face rather than recoil from it. This experience of untethering thoughts from physical reality through present-mindedness has been extraordinary, and I do hope to write in the future about it. But my recent trip to Karachi reminded me of the importance of being *transported*, and how there are specific kinds of distance that can bring clarity to life in a way that paying attention to what’s right before you never can.

It takes about a week for the spell that daily habits and concerns hold over me to dissipate. The gentle chaos of constant visitors to my grandmother’s house — the housekeeper, the cleaning lady, the tall man who brings bottled water for drinking, the short man who fills the water tank for the taps, the endless stream of aunts, uncles and cousins who come to say hello and goodbye — give the days a new rhythm. Life is spent running about town, gossiping and talking politics over tea and food. There’s also time for reading, chess, daydreaming.

I read Elena Ferrante and V.S. Naipul, local newspapers and history books. Ferrante and Naipul are trippy to read in these circumstances, since they’re such sharp observers of how place shapes identity. I think a great deal about how movement defines people: what it would have been like to grow up in Karachi — how different I’d be, how similar I’d be; my parents’ journey from Pakistan to England to America, and the audacity of building a life among strangers so far from home; how strange it is that Pakistan exists separately from India — the arbitrariness and the indelibility of it; how a rise in extremism and instability, fueled in part by the US-led war in Afghanistan, has made it harder for people to do as they wish in public.

I find Pakistan to be a surprising mirror into my personality, much the way that spending time with family members as I grow older tends to be. I say surprising because it entails noticing something about somebody else that I had thought of as my own trait, or at least a quality that I hadn’t considered the possible origins of. I chuckled as I remembered and recognized in myself the Pakistani farewell, which is essentially the antithesis of the Irish exit: a reluctant, lingering, comically drawn-out goodbye.

The concept of home is a complicated one for the children of immigrants, particularly those who grew up in the Global North but whose parents hail from the Global South. In popular discourse, these children have to “juggle two cultures” and feel pressure to strike a balance between the two. The term “American-born Confused Desi” explicitly frames this identity as a disorienting struggle for South Asian Americans.

The ABCD thing never resonated with me as I grew up. The fact that I didn’t fit neatly into America or Pakistan wasn’t a source of angst, but rather a gateway to liberation. One summer in Karachi when I was a teenager, my grandfather prodded me into realizing that it was not honorable to commit to values that one holds merely through the accident of birth. Islam was the first thing to slip away, but among other things there was also the collapse of international borders. I found that an identity forged around my beliefs and ideas and interests and the people I truly got on with was a natural way to find a place in the world. All this is to say that instead of feeling incomplete or homeless, I realized that it’s possible to build your own home with beams and bricks and shingles scattered around the world. I’ve found some of them in England, Colombia, Russia and elsewhere.

Before I left Karachi, I visited my grandfather’s grave. There was a mix-up when we entered the huge, disorderly graveyard, and we had trouble locating his tomb at first, having entered through the wrong gate. A custodian walked up and asked us who we were looking for. We told him and he repeated the name slowly, looking pensive. He wasn’t sure where we should go. We left that area and entered through another gate. My cousin was now sure we were on the right path, and we walked past graves polished and neglected. We found my grandfather’s tomb, which sits upon a hill overlooking the city. We stood next to it for a while; it was almost exactly five years after his passing. The sun was out, and an eagle circled overhead. Karachi, always bursting with life, felt quiet. I felt a heaviness in my chest, and then I felt the wind.

Newsletter: Joe Biden is exploding the theory that he’s the most electable Democrat

This is an essay from my weekly newsletter, which you can read in full here and subscribe to here.

Countless Democrats champion Joe Biden as the most “electable” candidate against Donald Trump. But the events of the last week alone illustrate just how rickety that theory is.

Last week the former vice president begged ultra-wealthy donors on the Upper East Side of Manhattan to support him and promised them that “nothing will fundamentally change” about their status in society. He also waxed nostalgic for a time where “civility” reigned in politics even as he worked with segregationists, and awkwardly reminisced about how the viciously racist Sen. James Eastland used to call him “son” instead of “boy.” And at a forum hosted by the Poor People’s Campaign he promised that he could break congressional gridlock by making efforts to “shame people” like Senate Majority Leader Mitch Mconnell into cooperation before a plainly skeptical audience.

These statements raise serious questions about Biden’s alleged lock on “electability.” I should note that the concept of electability, which tracks quite a bit with the hateful idea of “likability,” tends to buttress status quo thinking, gives an edge to white males, and leads people astray analytically — who thought Obama or Trump were highly electable during their primaries or general elections? But for the sake of engaging directly with proponents of this idea, let’s grant that electability is knowable and desirable. Recent events are a reminder that nobody should be confident that Biden has any special claim to it.

That’s because being eminently electable isn’t just about winning over moderates, it’s also about inspiring your base to vote for you in the first place. Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss is a clear cautionary tale: Four million Obama voters, disproportionately young and non-white and fairly liberal, stayed home instead of voting for her. Given that Clinton lost by some 80,000 votes in three swing states, polling experts estimate that her inability to motivate registered Democrats to show up for her is a reason she lost the election. Biden’s sycophancy toward the 1%, his tone deaf ear on racial politics, and his naivete about the nature of power are liabilities for a candidate who must mobilize an increasingly liberal and diverse base in huge numbers in 2020. Remember: Trump caused Republican turnout to surge in the 2018 midterms — he’s not to be underestimated. In that context, electability isn’t just about being able to schmooze with blue collar voters in the Rust Belt, it’s about having your finger on the pulse of your own party. Continue reading “Newsletter: Joe Biden is exploding the theory that he’s the most electable Democrat”

Newsletter: Everybody’s a cop

This is an essay from my weekly newsletter, which you can read in full here and subscribe to here.

Last week I read this remarkable story about how a new author tweeted something petty and nasty about a Metro worker in D.C., elicited a public backlash characterizing her as racist, and then had a distributor of her debut novel cut off ties with her, all in a matter of hours. And all I can say is: a pox on all your houses. Continue reading “Newsletter: Everybody’s a cop”

Bernie’s big speech was about taking back the idea of “freedom”

I wrote an analysis of Bernie’s hotly anticipated speech on democratic socialism for Pacific Standard. Here’s an excerpt:

When critics of socialism warn against its dangers, they often invoke communist tyrants of the 20th century. So when Senator Bernie Sanders delivered a major speech on Wednesday about what democratic socialism means to him, those critics may have been surprised to hear that “freedom” was his watchword.

“What I believe is that the American people deserve freedom—true freedom,” Sanders said to an audience of supporters at George Washington University. “Freedom is an often-used word, but it’s time we took a hard look at what that word actually means. Ask yourself: What does it actually mean to be free?”

Sanders went on to list nearly a dozen examples illustrating how economic insecurity—in the form of low wages, unaffordable health care, meager pensions, and the like—is incompatible with anything that could be considered a free life. Moreover, Sanders said, this is by design: “Many in the establishment would like the American people to submit to the tyranny of oligarchs, multinational corporations, Wall Street banks, and billionaires.”

Sanders’ argument that democratic socialism is the path to true freedom is shrewd messaging: It’s an attempt to flip conservative talking points about socialism on their head, and to re-appropriate freedom as a principle of the left. It also allows him to sidestep interminable debates about what really counts as socialism by anchoring his ideology in a quintessentially American tradition of liberty.

Newsletter: What happened to Ta-Nehisi Coates?

This is an essay from my weekly newsletter, which you can read in full here and subscribe to here.

As far as I can tell, Ta-Nehisi Coates has disappeared from the world of journalism. He deleted his Twitter account in 2017 and resigned from The Atlantic in the summer of 2018. He is still writing — he’s reportedly working on film, television, and comic book projects and he has a forthcoming novel — but for the moment he has no public perch from which he routinely offers essays and reportage on America politics and identity as he used to.

Some people see this as the loss as one of the country’s greatest commentators. But I think it might be a good thing that he’s stepped away.

This isn’t to say that I don’t miss Coates’ writing. I certainly wish I could still watch him think out loud. I feel the absence of his epic lyricism and sanguinary preoccupations, influenced by his consumption of Civil War history, hip hop, Shakespeare, and comic books. I was very fond of his blog at The Atlantic, which was uniquely dialogic in nature. Coates engaged in careful conversation with books he was reading, songs he was listening to, the thinkers he disagreed with or found interesting, and the huge set of commenters on his blog. Technically all public intellectuals are meant to be doing this, but in reality very few do it in a manner that’s so fruitful for the reader. Unlike most journalists and essayists, Coates felt no shame admitting agnosticism or non-expertise or even total ignorance on a variety of subjects. Whereas most of his counterparts either cover up or distract from being out of their intellectual comfort zones, he saw those situations as learning opportunities, and reveled in embracing the mindset of the student, in channeling “the magic of childhood.” How many people whose job requires a reputation of intelligence film themselves stumbling confusedly through a foreign language they had just begun learning? (I can assure you nobody will see any such thing from me as I study and butcher the language of Spanish these days.) And in the instances when he had total clarity regarding an idea or an event, he was masterful at interweaving lived experience with the abstract.

I diverged from Coates on many issues. I found his work to often elide human agency and to imbue the horrors of American racism with a kind of mystical and transcendent quality. Despite grounding his analyses in historical context and grappling with the corporeal aspect of white supremacy, I found his writing to engage inadequately with the workings of political economy. I will have to revisit Between the World and Me, but in my initial reading — which I found far less compelling than his blog posts and shorter essays — I found no persuasive theory of change. Yet because Coates is such a pleasure to read and so deliberate with his chisel, even the writing I disagreed with was enjoyable, and a surefire way to sharpen my own thinking.

I miss his blogging, but it might be a good thing that he’s taken a break from the conventional journalistic world. Ta-Nehisi Coates had become larger than life. His fans had formed a religion around him and his work. Many of his critics reserved special stores of venom for him that were overly personal. I came to believe that both those who revered him and loathed him were suffering from the same affliction: they were trying to extract too much from one man.

Continue reading “Newsletter: What happened to Ta-Nehisi Coates?”

Newsletter: Venezuela Q&A with Alejandro Velasco

On January 23rd, Juan Guaidó, the head of Venezuela’s opposition-controlled legislative branch, declared himself president of Venezuela. Within minutes, the US and several Latin American countries recognized him as Venezuela’s interim president and simultaneously rejected the legitimacy of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s sitting president who had been sworn into office for his second term earlier in the month. Since then, tensions have escalated as the US has imposed harsh new sanctions on Caracas and has boasted that military intervention is on the table.

As with all news related to Venezuela in the West, there’s a ton of glib analysis out there tainted by a reflex to treat the country as a battleground for narratives on socialism or foreign intervention, and there’s a scarcity of specific engagement with the Venezuelan experience. To cut through the noise last week I called up Alejandro Velasco, a Venezuelan historian of Latin America at NYU, to get his perspective on what’s driving this extraordinary turn of events, how the US left should be positioning itself on the issue, and why he feels overwhelmed by pessimism about his home country.

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

ZA: How does someone who hasn’t been a presidential candidate simply declare himself president?

Alejandro Velasco: That has to do with a particular reading of the Venezuelan constitution that says when there’s a vacuum in the executive power, then it falls upon the president of the National Assembly, Venezuela’s legislative branch, to assume those duties.

The legitimacy at the international level is being claimed upon by appealing to Article 233 of the constitution. They claim, not without reason, that the elections that brought Maduro last year into office were highly irregular, were fraudulent, and so therefore he is not a legitimate president as of January 10th, when he swore himself into a new term of office.

It’s a legal argument that Guaidó’s banking on to assert legitimacy. The problem is that same Article 233 of the constitution also says new elections need to be held within 30 days. Even though Guaidó has said the plan is to hold elections, it’s been very vague. In fact it’s the third of 3 plans that he’s announced. (The first one is seizing the usurpation, the second one is establishing an interim governments.) The argument makes sense insofar as you won’t be able to call new elections with the existing institutional apparatus, which is controlled by chavistas. But the second you say that then you get into all sorts of legal confusion as to why are you calling upon this article in order to assert the legitimacy of rule.

Which is why it’s important to understand that what’s happening in Venezuela isn’t actually a matter of legality, it’s a matter of who can claim legitimacy of rule.

Continue reading “Newsletter: Venezuela Q&A with Alejandro Velasco”